What is Reverse Engineering?

Reverse engineering is the process of analyzing a system—whether it's software, hardware, or even a physical object—to understand its inner workings, design, and functionality. This process involves taking something that has already been built and breaking it down into its fundamental components to figure out how it operates. It's like taking apart a clock to see how all the gears work together. In this post, we'll cover the basics of reversing and binary exploitation. But first, what is a binary?

A binary is the compiled, executable form of source code. When developers write programs in languages like C, the human-readable source code isn't directly executed by the computer. Instead, it's compiled into machine code - a binary file that the computer's processor can understand and execute. Binary exploitation refers to the process of identifying and leveraging vulnerabilities in compiled programs. In many software applications, bugs or flaws exist in the code. These bugs can create unintended behaviors or security weaknesses that attackers can exploit. By carefully analyzing and manipulating these vulnerabilities, an attacker can potentially force the binary to execute arbitrary code of their choosing. This means they can make the program perform actions outside its intended functionality, effectively gaining control over its behavior. This process lies at the heart of many cybersecurity attacks and is a critical area of study in reverse engineering.

Why is Reverse Engineering Important?

Reverse engineering is used in various industries for different purposes:

- Cybersecurity Analysis: By reverse engineering malicious software (malware), security professionals can identify vulnerabilities and develop patches to protect systems from attacks.

- Malware Research: Understanding how malware operates allows researchers to create effective countermeasures and antivirus solutions.

- Software Cracking: Reverse engineers can bypass software licenses and restrictions, allowing them to use software without paying for it.

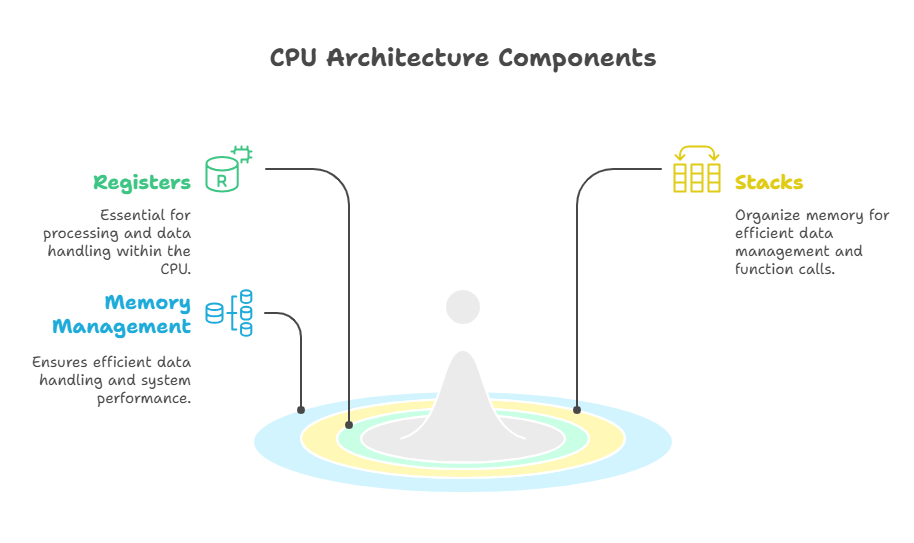

CPU Fundamentals: Registers and Memory Management

To understand reverse engineering, you need to have a basic understanding of how CPUs work. The CPU is the brain of a computer, responsible for executing instructions. One of the key components of a CPU is its registers, which are small storage locations that hold data temporarily during processing. These are the most important registers you need to know:

| Register | Purpose |

|---|---|

| rbp | Base Pointer - points to the bottom of current stack frame |

| rsp | Stack Pointer - points to the top of current stack frame |

| rip | Instruction Pointer - points to the instruction to be executed |

General Purpose Registers

These registers can be used for various purposes:

- rax, rbx, rcx, rdx

- rsi, rdi

- r8, r9, r10, r11

- r12, r13, r14, r15

In x64 Linux, function arguments are passed through registers in this order:

- rdi: First Argument

- rsi: Second Argument

- rdx: Third Argument

- rcx: Fourth Argument

- r8: Fifth Argument

- r9: Sixth Argument

A function's return value is always stored in the rax register.

Register Sizes

Here's a clearer way to understand register sizes:

| 8 Byte (64-bit) | 4 Byte | 2 Byte | 1 Byte |

|---|---|---|---|

| rax | eax | ax | al |

| rbx | ebx | bx | bl |

| rcx | ecx | cx | cl |

| rdx | edx | dx | dl |

| rsi | esi | si | sil |

| rdi | edi | di | dil |

| r8 | r8d | r8w | r8b |

| r9 | r9d | r9w | r9b |

| r10 | r10d | r10w | r10b |

| r11 | r11d | r11w | r11b |

| r12 | r12d | r12w | r12b |

| r13 | r13d | r13w | r13b |

| r14 | r14d | r14w | r14b |

| r15 | r15d | r15w | r15b |

For example, when using rax:

- rax: full register (8 bytes)

- eax: lower 4 bytes

- ax: lower 2 bytes

- al: lowest byte

Words

You might hear the term word, a word is just two bytes of data (depends on the architecture):

- Word: 2 bytes of data

- Dword: 4 bytes of data

- Qword: 8 bytes of data

Memory Organization Principles

Memory in a computer is organized in a specific way, and understanding this organization is crucial for reverse engineering. One important concept is endianness, which refers to how data is stored in memory.

; Little-Endian Example (x86)

mov dword [0x1000], 0x12345678

; Memory contents at 0x1000:

; 78 56 34 12In the example above, the value 0x12345678 is stored in memory starting with the least significant byte (78) at the lowest address (0x1000). This is known as little-endian format, which is used by x86 processors. In contrast, big-endian systems store the most significant byte first.

But what is the stack?

The stack is used to store temporary data, such as function arguments, return addresses, and local variables.

It's a LIFO (Last In, First Out) data structure, meaning that the last item added to the stack is the first one to be removed, data is pushed onto the stack using the push instruction and popped off using the pop instruction.

The CPU uses the stack pointer (ESP) to keep track of the top of the stack and the base pointer (EBP) to reference the current stack frame.

Function Call Stack

Let's say a function in our compiled code is called, the CPU performs a series of operations to set up the stack frame:

push ebp ; Save previous base pointer

mov ebp, esp ; Establish new stack frame

sub esp, 0x10 ; Allocate 16 bytes for localspush ebp: This instruction saves the current base pointer (EBP) onto the stack. This allows the function to restore the previous stack frame when it returns.mov ebp, esp: This sets the new base pointer to the current stack pointer (ESP), effectively creating a new stack frame.sub esp, 0x10: This allocates 16 bytes of space on the stack for local variables.

Stack Frame Visualization

Here's how the stack looks after the function prologue:

High Addresses

+------------------+

| Previous Data |

+------------------+

| Return Address | ← rbp + 8

+------------------+

| Saved rbp | ← rbp

+------------------+

| Variable 1 | ← rbp - 8

+------------------+

| Variable 2 | ← rbp - 16

+------------------+

Low Addresses ← rsp- Return Address: This is the address where the CPU should jump back to after the function finishes.

- Saved EBP: This is the previous base pointer, saved so that the function can restore the caller's stack frame when it returns.

- Local Variables: These are variables that the function uses during its execution. They are stored below the saved EBP.

Assembly Language Fundamentals

Assembly language is the human-readable form of machine code, which is the language that the CPU understands directly. Learning assembly is essential for reverse engineering because it allows you to understand what a program is doing at the lowest level.

Essential Instruction Types

Here are some common types of instructions you'll encounter in assembly:

; Data Movement

mov eax, [ebx+4] ; Load from memory address EBX+4

lea ecx, [eax*2] ; Calculate address without memory access

; Arithmetic Operations

add edi, 0x10 ; EDI = EDI + 16

sub esp, 0x20 ; Allocate 32 bytes on stack

; Control Flow

jmp 0x80483fb ; Unconditional jump

cmp eax, ebx ; Compare registers

je label_equal ; Jump if equalExplanation of Instructions

mov eax, [ebx+4]: This instruction moves the value stored at the memory addressEBX + 4into the EAX register.lea ecx, [eax*2]: This calculates the addressEAX * 2and stores it in the ECX register without accessing memory.add edi, 0x10: This adds 16 (0x10 in hexadecimal) to the EDI register.sub esp, 0x20: This subtracts 32 (0x20 in hexadecimal) from the stack pointer (ESP), allocating space on the stack.jmp 0x80483fb: This causes the CPU to jump to the instruction located at address0x80483fb.cmp eax, ebx: This compares the values in the EAX and EBX registers.je label_equal: This jumps to the labellabel_equalif the previous comparison resulted in equality.

Real-World Disassembly: Hello World

Let's take a look at a simple "Hello World" program disassembled into assembly:

080483fb <main>:

80483fb: 8d 4c 24 04 lea ecx, [esp+0x4]

80483ff: 83 e4 f0 and esp, 0xfffffff0

8048402: ff 71 fc push DWORD PTR [ecx-0x4]

8048405: 55 push ebp

8048406: 89 e5 mov ebp, esp

804840c: 68 b0 84 04 08 push 0x80484b0 ; "hello world!"

8048414: e8 b7 fe ff ff call 80482d0 <puts@plt>

8048419: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax, 0x0

8048421: 8b 4d fc mov ecx, DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

8048425: c3 retKey Execution Steps

- Stack Alignment Preparation: The program aligns the stack to ensure proper memory alignment.

- Argument Pushing for

puts(): The string"hello world!"is pushed onto the stack as an argument for theputs()function. - Function Call Setup and Cleanup: The

puts()function is called, and the stack is cleaned up afterward. - Return Value Initialization: The program sets the return value to

0(indicating successful execution) and returns control to the operating system.

Essential Reverse Engineering Toolkit

To perform reverse engineering effectively, you'll need a set of tools that allow you to analyze binaries both statically (without running them) and dynamically (while they're running).

Static Analysis Tools

Static analysis involves examining a binary without executing it. This can give you insights into the structure of the program, such as its functions, strings, and imports.

$ file target_binary

target_binary: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linkedfileCommand: This command identifies the type of binary you're working with. In the example above, the binary is an ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) file, which is common on Linux systems.

$ strings -n 8 target_binary | grep -i "http"

https://malicious-domain.com/c2-serverstringsCommand: This extracts readable strings from the binary. In this case, we're looking for URLs or other suspicious strings that might indicate malicious behavior.

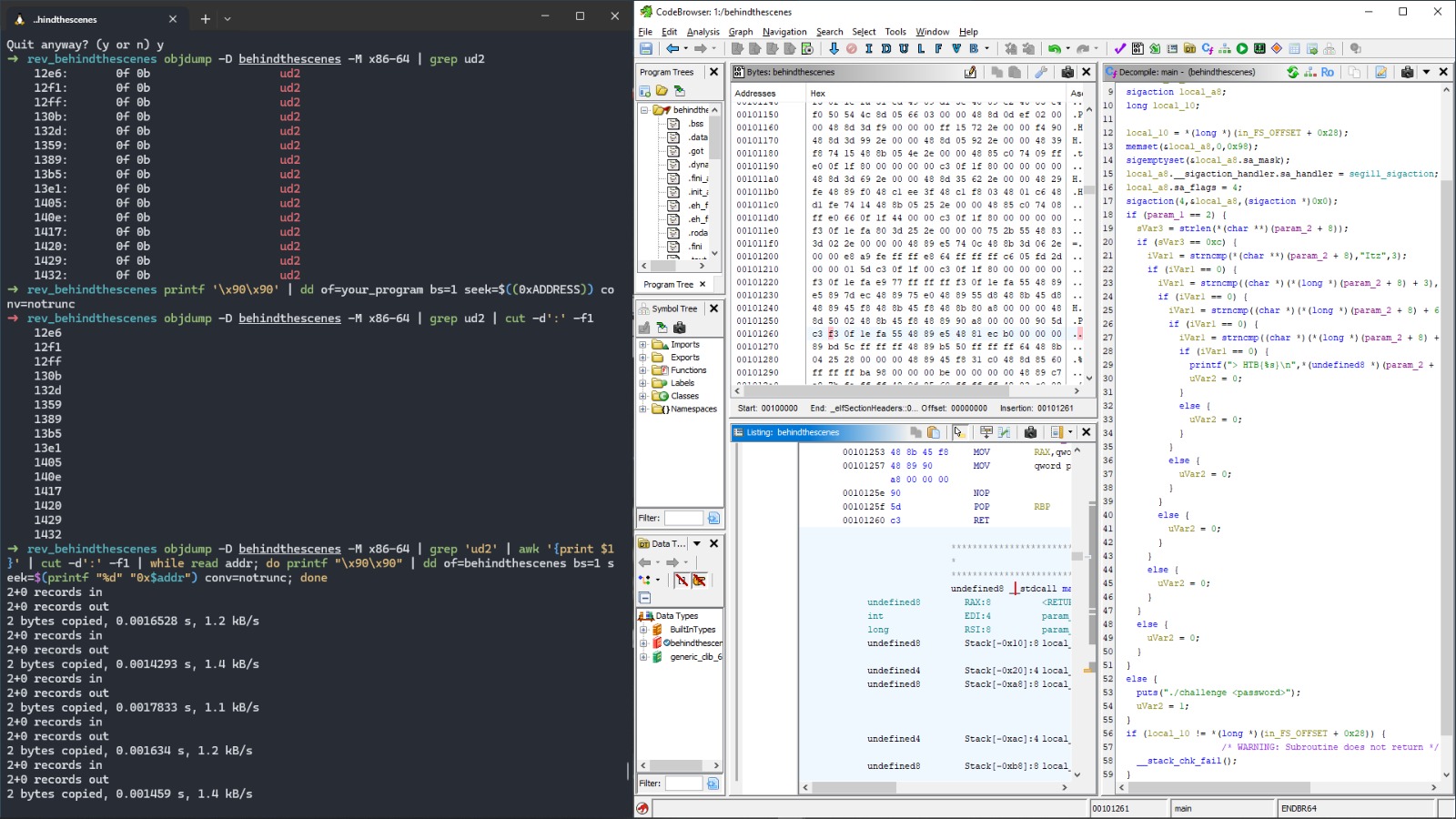

You can alse use 'xxd' to view the binary in hex format and 'objdump' to view the disassembly. One of the most popular tools for static analysis is 'IDA Pro', but there are other tools like 'Ghidra' and 'Radare2' that are also great. Here is an example of ghidra decompiling a ctf challenge binary, you can see the function names and the code is more readable.

Dynamic Analysis Workflow

Dynamic analysis involves running the binary and observing its behavior. This can help you understand how the program interacts with the system, such as making network requests or modifying files.

GDB Basic Commands

GDB (GNU Debugger) is a powerful tool for dynamic analysis. Here are some basic commands you can use:

(gdb) break *0x0804840c # Set breakpoint at push instruction

(gdb) run # Start execution

(gdb) x/s $ebp-0x4 # Examine string argument

(gdb) info registers # Display register statesbreak: Sets a breakpoint at a specific memory address.run: Starts the program execution.x/s: Examines the string at a specific memory address.info registers: Displays the current state of the CPU registers.

Pwn Tools

Pwntools is a python ctf library designed for quick exploit development and reverse engineering:

$ pip install pwntools

python3

>>> from pwn import *

>>> p = remote('./target_binary') # run a target binary

>>> gdb.attach(p) # attach the gdb debugger to a process

>>> p.send(x) # send a string to the process

>>> print(p.recvline()) # print the output of the process

>>> p.interactive() # interact with the processReverse Engineering Methodology

Reverse engineering is a systematic process that involves multiple steps. Here's a general methodology you can follow:

Systematic Analysis Process

-

Binary Acquisition

- Obtain clean copies of the binary through legal means.

- Verify the integrity of the binary using cryptographic hashes (e.g., SHA-256).

-

Initial Triage

$ binwalk -ME target_binary # Extract embedded files $ rabin2 -I target_binary # Show binary headersbinwalk: This tool helps you extract embedded files or resources from the binary.rabin2: This displays information about the binary, such as its headers and sections.

-

Control Flow Analysis

- Identify the main functions of the program.

- Map cross-references between functions.

- Annotate function parameters and return values.

-

Behavioral Analysis

- Monitor file system changes.

- Capture network traffic.

- Log system calls to understand how the program interacts with the operating system.

Conclusion: Building Reverse Engineering Expertise

Mastering reverse engineering requires a combination of skills, including pattern recognition, persistence, and tool proficiency. It's a challenging but rewarding field that opens up many opportunities in cybersecurity, software development, and beyond.

Recommended Learning Path

- Master Assembly for Your Target Architecture: Start by learning assembly language for the architecture you're interested in (e.g., x86, ARM).

- Practice with CTF Challenges: Capture the Flag (CTF) challenges, such as Crackmes, provide hands-on experience with reverse engineering.

- Study Real-World Malware Analysis Reports: Analyze reports from cybersecurity firms to understand how professionals reverse engineer malware.

- Contribute to Open-Source Reversing Tools: Get involved in open-source projects to improve your skills and contribute to the community.